Rob. Walton talks with addicted semantic fanatics and crusading new wave cruciverbalists

S

ome only dabble in it. Others are addicts who crave a daily fix. Armed with newspapers, magazines, books and pencils (pens for the bold ones), an unorganized army of crossword puzzle enthusiasts grapples with the grid daily.

No one has determined precisely how many crossword puzzlers there are in America — it’s a disjointed hobby usually practiced alone. Recent surveys, however, put the estimate at roughly 27 million regular crossword workers in the United States. The figure is twice as large if you count the occasional indulger. Soldiers of this invisible army can be spied, pencils poised, on the train, in the elevator, at the pool and in front of the television — seizing any sedentary moment.

The proliferation of puzzle books and the emergence of crossword hybrids indicate that the popularity of crosswords is increasing, and hobbyists are ever seeking newer and tougher challenges.

Last December, the modern crossword puzzle celebrated its 75th anniversary. According to most sources, the first puzzle appeared in the New York World on Dec. 21, 1913. The diamond-shaped “Word-Cross,” created by magazine editor Arthur Wynne, was a grid of interlocking words with 31 clues.

Games magazine, perhaps the foremost authority on puzzles extant, suggests that the first crossword may have been a lesser known puzzle debuting in People’s Home Journal in September 1906. Skeptics argue that this unbounded puzzle was not a true crossword because it did not include blackened squares.

Regardless, crosswords have endured the test of time, and they continue to evolve. Newer, more challenging hybrids, some with blank grids, others involving puns and wordplay, are recruiting a new generation of followers.

Regardless, crosswords have endured the test of time, and they continue to evolve. Newer, more challenging hybrids, some with blank grids, others involving puns and wordplay, are recruiting a new generation of followers.

The hottest news in crossworld is a controversy between the traditional school of cruciverbalists (crossword puzzle makers) and an emerging “new wave” of constructors. The old school believes trade names and trendy popular culture should be off-limits within the scope of the puzzle.

New wavers, on the other hand, believe puzzles should reflect the contemporary language of most Americans — common slang, proper nouns and trade names.

Stanley Newman, president of the American Crossword Federation, steered me toward “the youngest crossword puzzle creator in the country,” an up-and-coming personality in the crossword community and an unofficial spokesperson for the new wave.

Trip Payne is a 21-year-old senior majoring in English at Emory University who has been constructing puzzles for six years. He just completed his third year of a summer internship at the esteemed Games magazine in New York City.

“I am on the new wave side of crosswords, as opposed to the traditional,” Payne said. “I encourage modern references to movies, songs and pop culture.”

The ongoing controversy over changing mores has been monikered the “oreo war,” prompted by an argument involving the four letter answer, “O-R-E-O.” To arrive at the solution, the old school, insists the clue should be, “mountain: comb. form,” as in oreopithecus (mountain ape) or oreortyx (mountain quail). But try to locate either of these words in your Webster’s.

New wavers suggest an appropriate clue would “cookie,” referring to the trademarked chocolate sandwich cookies.

Adhering to the new wave principles, Payne’s main concern in creating and editing puzzles is ensuring that they are entertaining and challenging. As opposed to clues that are simple synonyms, Payne prefers ones that make lively references. “‘DOG’ should be something like ‘shepherd or schnauzer’ as opposed to ‘canine,’” he explained.

Adhering to the new wave principles, Payne’s main concern in creating and editing puzzles is ensuring that they are entertaining and challenging. As opposed to clues that are simple synonyms, Payne prefers ones that make lively references. “‘DOG’ should be something like ‘shepherd or schnauzer’ as opposed to ‘canine,’” he explained.

In his puzzles, Payne makes modern references to television, movies and pop songs in addition to the traditional old school references to sports, literature and opera. He avoids using too many references from the same field.

To reinforce his position, Payne expresses an aversion to what he calls “bad words.” These include medieval or archaic words which have atrophied from the body of English vernacular. To new wavers, esne (an old English word for “serf”) is truly a four-letter word.

Although Payne admits to an above-average vocabulary, he will not include words that a solver shouldn’t be reasonably expected to know. An example of verboten verbiage is “abri” (a hillside dugout), which is a mainstay in such traditional puzzles as those appearing in The New York Times.

“Eugene T. Maleska [editor of The New York Times' crossword] would rather use crosswords to teach. He would rather use boring words like obscure geographical references,” Payne said. (Scandinavian river tributaries are not uncommon in the Times.)

Payne doesn’t think it should be necessary to do research in order to complete a puzzle.

Will Weng, former crossword editor of The New York Times, sheds a different light on the matter. “The new wave is not as new as you think it is. We have always used names like Kodak and Vaseline. This is OK for books and magazines, but we didn’t do it in the newspaper because it seemed as though we were promoting a company.

“The difference is the new generation is asserting itself,” he added.

And he’s right. Evidence suggests that the new wave is permeating even the strictest of venues. Payne recently substantiated his argument against the use of antiquated words with a characteristic example. To arrive at the answer “A-L-A-R,” he said, traditionalists would supply the clue “winged,” a definition one would be hard-pressed to find in a household dictionary. The new wave school would use “pesticide” as the clue, referring to the news-making chemical sprayed on apples.

And he’s right. Evidence suggests that the new wave is permeating even the strictest of venues. Payne recently substantiated his argument against the use of antiquated words with a characteristic example. To arrive at the answer “A-L-A-R,” he said, traditionalists would supply the clue “winged,” a definition one would be hard-pressed to find in a household dictionary. The new wave school would use “pesticide” as the clue, referring to the news-making chemical sprayed on apples.

Days after our conversation, alar appeared in the Times, clued by “controversial pesticide.” The Times, they are a changin’.

I

n his youth, Payne was interested in crossword puzzles and other word games. Inevitably, he decided to try his hand at constructing one of his own. Six years ago he submitted his first puzzle to Games.

The puzzle was returned, unaccepted. The rejection letter said that it was an interesting idea, but that it didn’t quite go by the rules. An enclosed spec sheet outlined precise qualifications regarding symmetry, number of allowable black squares, etc. He followed the instructions, and his next puzzle was accepted.

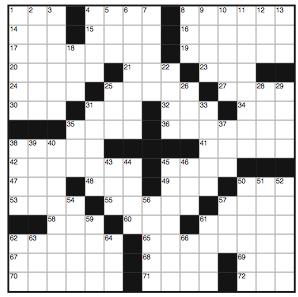

Payne described the process of creating a crossword. “To construct a puzzle, you start with a theme, create a set of events. Then you make a grid.” As if to complicate matters, he reminded me that, “A true crossword is symmetrical.

“You start with several words that will fit symmetrically into the grid,” Payne continued. “Then you start filling in the smaller words around it. After doing it for a while, you learn where the black squares will go. I do the clues last.”

A daily puzzle (15 by 15 squares) takes about three to four hours to construct. A Sunday size, which is considerab1y larger, can take a couple of days.

Although Payne is now a crossword editor and a constructor, he still likes to solve. Basic crosswords, as opposed to cryptics or acrostics, are his favorite. Following graduation, Payne plans to pursue a career in the puzzle world.

M

ost newspapers and magazines carry some sort of crossword puzzle. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution run syndicated puzzles. Since it was bought out by The New York Times two years ago, the Gwinnett Daily News has carried the Times puzzle, in addition to another syndicated puzzle. Neither newspaper knows exactly how many readers attempt their puzzles, but both recount horror stories involving a deluge of irate phone callers when a puzzle was inadvertently omitted or misplaced.

I don’t know how many people work it,” said Susannah Vesey, layout editor at the AJC. “I got a huge amount of calls when I started putting it in the middle of the page. People couldn’t fold it. I’ll never do that again.”

“They light up the switchboard if we put a wrong answer in,” said a crossworker at Gwinnett Daily News. “There is a large vocal contingent who work it.”

Sophisticated crossworders tend to be critical of newspaper syndicates. “There are five or six crossword syndicates, among them King Features Syndicate, LA Times and United Media Syndicate,” said Stanley Newman, president of the American Crossword Federation. “The problem is, there is no licensing organization or trade magazine.”

“They do the same things they did 30 or 40 years ago. And. they continue to sell them to newspapers because they can’t tell the difference,” he expounded. “They are laden with mistakes and tend to be unimaginative.”

Newman’s organization offers a challenging alternative to the daily newspaper routine. The American Crossword Federation, with a membership of over 2,000, provides subscribers with a bimonthly newsletter and 72 puzzles a year for an annual fee of $20. Newman, who is also editor for New York Newsday‘s Sunday puzzle, describes the federation’s puzzles as much harder than typical newspaper or magazine puzzles. Their puzzles are ranked in five levels of increasing difficulty: Puzzler, Middler, Expert, Master and Grand Master.

The newsletter is a primary source of crossword current events such as tournaments and ACF-sponsored crossword cruises.

In Connecticut, The Crosswords Club, boasting a membership of almost 30,000, supplies subscribers with four Sunday-size puzzles per month for an annual fee of $20.

“We offer an upscale series of crossword puzzles printed individually on high quality paper,” said Paula Hager, president of the Crosswords Club. “They are serially numbered, and the solutions come with comments by editor Will Weng.”

“They’re not the hardest — they’re good quality puzzles and they’re challenging. The clues are clever, imaginative, entertaining and challenging,” she added.

Cashing in on the success of these two ventures, The Crossword Puzzle of the Month Club has recently gotten underway in Illinois.

Y

our average crossworder simply works the daily puzzles in his or her idle time. Local retiree Ruth Mohan has been doing the daily crosswords for as long as she can remember. She solves the puzzle every day, and if she can’t finish, she saves it and checks it against the solution the next day.

Mohan used to have a crossword puzzle dictionary to help her — she has long since set it aside. She also used to keep running lists of foreign words, but she doesn’t need to refer to them anymore, either.

“I’m not that good,” she conceded. “I’m not a whiz. I like it when they’re easy.”

Other crossworders prefer their puzzles nice and rough. Charles’ Boelkins, a 50-year-old woodworker in Conyers, describes crosswords as “aerobics for the mind.”

Like most addicts, he started with the daily newspaper. “I started doing them with a vengeance about 10 years ago when I decided to take a midlife segue from the academic setting.” Boelkins was a senior research associate at Harvard before he decided to change vocations.

When he became inured to the dailies, he joined the American Crossword Federation, a national crossword club which supplies 12 puzzles every other month. Occasionally, he ventures into Atlanta to stock up on puzzle books.

When he became inured to the dailies, he joined the American Crossword Federation, a national crossword club which supplies 12 puzzles every other month. Occasionally, he ventures into Atlanta to stock up on puzzle books.

“Oxford Book Store is the only place to buy puzzle books in the city,” Boelkins said. “They carry a huge selection of good, high quality, difficult puzzle books.” His favorites are The Pen and Pencil Club series and Bullseye, both published by Running Press out of Pennsylvania.

Boelkins would also love to compete, but there are no tournaments in the area. In fact, the only contests in the United States are held in the northeast corridor, between New York and Boston. The Stamford Marriott Crossword Puzzle Tournament in Connecticut is perhaps the oldest and most widely known – 120 contestants from coast to coast compete annually. The Long Island Crossword Open and the North Jersey Crossword Open also boast about 120 participants each year. Some small towns in Cape Cod sponsor local tournaments. The United States Crossword Open, which was held annually in New York City, died in 1986 due to lack of sponsorship.

Lois M. Strom, who just relocated to Gainesville from Dunwoody, has competed in crossword competitions in New York.

“I have been in some tournaments, but I don’t get anywhere near the winning area,” she said.

Strom explained how she came to the competitive level.

“For a tournament sponsored by Games, I completed one qualifying puzzle in the back of the magazine. I made it. Then I was sent a series of four graduated puzzles.”

“Just qualifying was an achievement. But the fourth puzzle really separated the men and women from the boys and girls,” she boasted…modestly.

“I came in below the halfway mark as far as rating in the tournament itself,” she admitted. “There’s no chance of my ever being in the upper quarter.”

So what’s the appeal of crosswords for Strom? “I enjoy the English language for one thing. One requisite for being able to do crosswords and enjoy them is to have a good vocabulary. It helps to increase your vocabulary and teaches you to spell.”

For Strom, it’s almost a calling. “Like the mountain, it’s there. The grid of black and white squares is there just waiting to be filled in.”

![]()