Lynch Mob

Lynch Mob

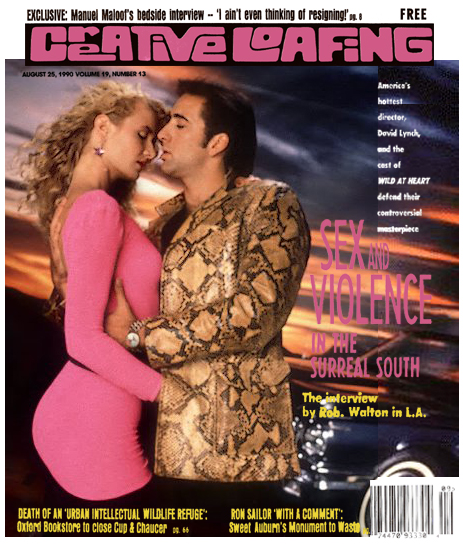

Opening amid controversy, critical acclaim and the national mania over Twin Peaks, Wild at Heart should be director David Lynch’s most successful film to date.

By Rob. Walton

In Steel Magnolias, one of the Southern belles chirps, “Laughter through tears is my favorite emotion.” A new Southern drama of another ilk evokes laughter through fear.

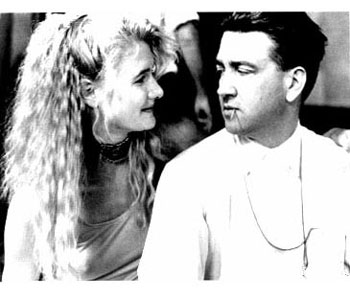

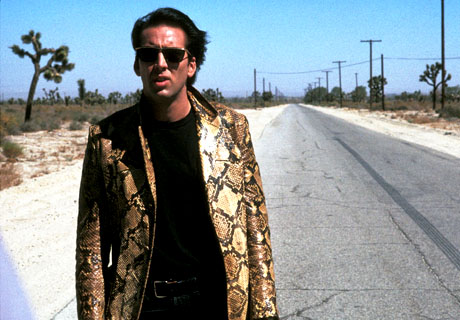

David Lynch’s Wild at Heart, an intense, surreal, American Gothic sort of road story starring Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern, sheds a completely different light on the American South. The opening scene, in which Cage literally dashes the brains out of a would-be assailant’s skull, sets the volatile, passionate and graphic tone of the movie.

Wild at Heart isn’t your run-of-the-mill splatter flick, however. It’s a first-class artistic and romantic picture directed by one of America’s few living auteurs. And it has made waves here in the U.S. and across the ocean for several reasons.

First and foremost, it’s directed by David Lynch, the warped genius behind the dark classics Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, Dune and Blue Velvet. The jack-of-all-media also pens the weekly comic strip “The Angriest Dog in the World” and has an album out featuring the vocals of Julee Cruise. Most recently, Lynch is red hot with the success of Twin Peaks, his surreal nighttime soap opera on ABC, a groundbreaking attempt to introduce surrealism into the living rooms of the bourgeoisie.

“I think the American public is so surreal, and the idea that they don’t understand surrealism is so absurd,” he says in a recent interview. “It’s just that they’ve been told that they don’t somehow, but you go anywhere and old-timers will tell you very surreal stories with strange humor and everybody’s got a friend who is totally surreal. And they understand it like everybody else.”

Does Lynch think Americans are ready for his brand of surrealism?

“You bet! That’s the next wave.”

Wild at Heart strolled away from the Cannes Film Festival this February with the coveted Palme d’Or – analogous to an international Best Picture Oscar. This is the second year in a row that an American film has walked off with the award; last year Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies and videotape narrowly won out over Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing.

Wild at Heart strolled away from the Cannes Film Festival this February with the coveted Palme d’Or – analogous to an international Best Picture Oscar. This is the second year in a row that an American film has walked off with the award; last year Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies and videotape narrowly won out over Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing.

But with all the acclaim, there is also controversy. When Bernardo Bertolucci announced the award, Lynch was met with a chorus of jeers to rival the cheers. The lead booer, apparently, was an incensed Roger Ebert.

The controversy didn’t stop in Cannes, either. There are even tougher critics in America. The film, upon review by the 11-member Motion Picture Association of America, was promptly stamped with an X rating for violence. And an X rating is considered a kiss of death to a commercial film – a sort of box office “scarlet A.”

Distributors deal with an X rating in different ways. They can go ahead and release the film with the X, which immediately disqualifies it from exhibition in many theater chains and dooms it to exhibition in independent houses, relatively few of which remain in the U.S. Further, many newspapers and TV stations won’t carry advertisements for X-rated movies, so it’s unlikely that anyone will even know if it’s playing.

Editors can re-cut a film to make the censors happy, as was done for De Palma’s Dressed to Kill, Lyne’s Nine and a Half Weeks and, most recently, Wild Orchid. Or the company can release a feature without any rating at all, as is done with many foreign films. This was the solution for recent problem movies like The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer and Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, all European imports or independents.

But Lynch was under contract to bring the film in with an R rating for the studio, and something had to be done without sacrificing quality or integrity. There are a flurry of rumors circulating about how the X rating was appealed, some of which include Lynch butchering his award-winning film to appease the censors. Lynch is eager to set the record straight about Wild at Heart.

“We submitted it many times to the board, and each time there were certain scenes that kept coming up,” Lynch tells me, referring to a graphic decapitation shot and a brutal torture scene.

“Our producers argued with them, and I had a couple of discussions with the board. At that same time we had to commit to making an answer print to get to the Cannes Film Festival, so we kind of put the board on hold for a while, got the film finished up and went to the Cannes. When we came back, we had to submit the picture again.”

This time, the board was a little more flexible, and with some minuscule alterations, was willing to rate it R.

“I think two things helped the situation,” Lynch says. “One was the sort of backlash from Total Recall, and the other was we won at the Cannes Film Festival.”

Lynch elaborates on the Total Recall reference.

Lynch elaborates on the Total Recall reference.

“The board has been giving X ratings to many films – films that had things that two years ago would have gotten by with an R. Everybody was wondering what was going on. Then suddenly, in the middle of all that, Total Recall came out, with – well, I haven’t seen the film – but, apparently some very heavy violent things. Everybody said, ‘Wait a minute, what’s the story here? Our film is getting an X, and Total Recall, with twice the number of horrible things, is getting an R.’ So I think the board did a little two-step and shifted a little.”

“It didn’t even ask us to cut any frames,” he claims. “They just finally agreed that we could put an overlay of smoke and fire over the two shots – an even, transparent overlay so you can see what was there – and it just obscures it slightly. It involved an overlay on one second of film, and not one frame was lost,” he stresses.

There were some other mitigating factors in the ratings decision, says leading lady Laura Dern. “They had some concerns about [costar Nicolas Cage]‘s and my sex scenes, but nothing has been changed of that. It disturbs me. I think that we were all upset by the controversy because I think that there has to be some consistency within the board, and there isn’t at this point. If you’re going to let one film go with extreme blood and gore and yet make David Lynch an example, it’s not appropriate just because he’s a ‘different’ filmmaker. I would think that the major box office, that’s more accessible to young teenagers, would be more of a concern than a David Lynch movie.”

Censorship and restrictions on the arts are hot issues these days, especially in the South, where rap group 2 Live Crew was arrested for its nasty lyrics, and shopkeepers have been cited for even selling the album. The South is currently the focal point for freedom of expression, at least concerning the commercial arts.

Atlanta is not without its own would-be arbiters of taste and morals. It was less than ten years ago that Fulton County solicitor Hinson McAullife raided George Lefont’s Screening Room for exhibiting The Story of 0, a film he deemed obscene because it had an X rating. (Lefont eventually won the case and continued to show the film).

The current conservatism regarding the commercial arts coincides with the raging N.E.A. controversy on Capitol Hill in which artists are being denied public funding because their art may be deemed offensive. Politician Tipper Gore’s Parental Music Resource Center is also quite vocal about the need to regulate what music our children have access to. The entire issue challenges the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of expression. How far should it go? Lynch elaborates on the fine line between censorship and restriction.

“I think that you have to be able to be free to do pretty much whatever you want. When it comes time to show what you’ve done, someone has to – that’s the purpose of the ratings – set a little bit of a guideline so the innocents don’t wander in and see something that would disturb them for the rest of their lives. In the case of any kind of thing like paintings or films or anything like that, you can have a little bit of a general rating, or a room for certain photos or something like this where people realize they’re going to see something heavier when they go in there. But you should be able to make whatever you want.”

“I think that you have to be able to be free to do pretty much whatever you want. When it comes time to show what you’ve done, someone has to – that’s the purpose of the ratings – set a little bit of a guideline so the innocents don’t wander in and see something that would disturb them for the rest of their lives. In the case of any kind of thing like paintings or films or anything like that, you can have a little bit of a general rating, or a room for certain photos or something like this where people realize they’re going to see something heavier when they go in there. But you should be able to make whatever you want.”

Wild at Heart, adapted by Lynch from the novel by Barry Gifford, is a stylized, cross-country romance about young love. Recently widowed Marietta Fortune (Diane Ladd) forbids her daughter Lula (Dern) to date Sailor Ripley (Cage), who has been convicted of manslaughter. When Sailor gets out of jail, the kids flee their hometown of Cape Fear and take to the road.

The kids cross Lynch’s Gothic rural South in a red 1965 Thunderbird convertible, guided by instinct more than intellect. Lula is a gum-smacking speed metal chick with a wardrobe of black leather bras and lace lingerie. She’s a sidewalk philosopher with a thought for everything. “The whole world’s Wild at Heart and weird on top!” she opines in a cheap motel, foreshadowing the twists of this eccentric love story.

Sailor Ripley is more of a passionate animal, not so much of a thinker. “The way your head works is God’s own private mystery,” he tells Lula. And he’s right. The two are made for each other. They are innocent, untainted youth.

Marietta, played by Dern’s real-life mother Diane Ladd, is well-taloned Southern white trash with a wig for every occasion and lipstick worn like blood after a kill. In her Max Factor fright makeup, she’s the Wicked Witch to Lula’s innocent Dorothy. Marietta dispatches a private detective after the young couple and, when he shows up empty-handed, she sends a hit man to bring her daughter back alive and alone.

Despite its extreme subject matter, Wild at Heart is a classic love story at its core. It’s a steamy Romeo and Juliet with a hint of The Wizard of Oz and a lot of Lynch. The kids are on the lam from the perversion and corruption of adulthood. Their flight leads them from the Carolinas to New Orleans and Texas.

On the road, Lula and Sailor encounter a cast of patented Lynch loonies – more adults who want to infect them with their evil. Willem Dafoe plays Bobby Peru, a rotten-toothed “black angel” who introduces violence and evil into Big Tuna, Texas. Peru’s girlfriend, Perdita Durango (Isabella Rossellini) and her sister Juana (Grace Zabriskie) are also sinister forces, dabbling in drugs, the occult and murder.

The film includes incidents of graphic sex, attempted rape, abortion, decapitation and ritual torture, few of which are actually part of Gifford’s book. By including such perverse and grotesque imagery, is Lynch not testing the limits of taste and taunting the censors?

“No,” he responds assuredly, “If you sit down before you shoot a scene and say, ‘Listen fellas, we’re going to test the limits of the M.P.A.A.,’ that’s totally the wrong way to do it. It’s trying to be true to the material and the ideas, and just doing them with some kind of power. Power is like a feeling. Like feeling something good or feeling something frightening. The beautiful thing about cinema is you can feel something.

Cage, however, feels that Lynch may indeed by testing the parameters.

Cage, however, feels that Lynch may indeed by testing the parameters.

“Maybe a little, but he knows where to bring it back,” he says. “The violence in the film is preposterous. It’s really ridiculous. It’s so blatant that it’s almost like a cartoon in a way. Excuse me, but it is kind of funny. It is ridiculous and at the same time scary. He’s able to mix absurd things with scary things or pure things. Even the love aspects of the movie can be absurd and also real or pure. He likes to mix it all up, and that way you cultivate a more universal feeling to the film, I think.”

Lynch did pare down some of the movie before he submitted it to the ratings board. The original running time, before extraneous scenes were deleted, was over four hours. The final running time is just over two hours. One particular scene that Lynch eliminated involved former Atlanta actress Grace Zabriskie and another actor feverishly kissing over the bloodied head of an executed man. Members of a test audience virtually fled the theater at this scene.

“David felt that he lost the audience with that,” admits Cage. “They weren’t with it. I would’ve liked to have seen it because I like extremes. I love to see what the parameters of what the distances are. It works the way it is, and in a way it’s even more frightening because the imagination is allowed to go on.”

Ladd, one of the evil characters in the picture, has a different philosophy on the nature of Lynch’s brand of violence. “We have a lot of violence in pictures today. Dave and I had a long discussion about this, and in this country of ours, you have the highest rate of suicide among young children, from 12 years old, Now this is an abomination.”

” … if you were really depressed and you were thinking about taking your own life, and you saw a David Lynch movie, would you do it? I don’t think so. Think about it.”

“A lot of these kids see violence on TV, and they see violence in films,” she continues with a Southern drawl. “Let’s face it, with some of the kids, Daddy says after the movie, ‘Well boy, tomorrow I’m taking you out and buying you a gun. Come on boy,’ and you see them buying everything to, like, kill. They don’t know that when they pull that trigger, that the blood spurts and the guts fall out. That is horrible. It’s horrible! It’s not a game. You don’t just go, ‘Oh-h-h,’ and die. I’ve done it. If they saw the violence…”

Ladd catches her breath. “Tell me, if you were really depressed and you were thinking of taking your own life, and you saw a David Lynch movie, would you do it? I don’t think so. Think about it.”

“When I see violence in a David Lynch movie, it makes me sick,” she continues, emphatically. “And violence should make you sick. And it should make our kids sick so they don’t want to do it, okay! So if David Lynch is showing violence the way it’s supposed to be, how come we’re all shocked? How come the biggest movies right now, $16 million – $22 million, have so much violence that your head boggles? And these are the pictures making the most money at the drive-ins for our teen-agers, etc. The reason [censors] say something is because David is giving you artistry at the same time. He’s giving you feeling at the same time. He’s not just going ‘buh-buh-buh-buh-buh!’,” Ladd points her index finger like a gun, “so you walk out and say, ‘Boy, let’s go get some more popcorn and watch it again!’ He’s giving you art. And in the middle of art, you’re also seeing life and violence. It makes me sick.”

“When I see violence in a David Lynch movie, it makes me sick,” she continues, emphatically. “And violence should make you sick. And it should make our kids sick so they don’t want to do it, okay! So if David Lynch is showing violence the way it’s supposed to be, how come we’re all shocked? How come the biggest movies right now, $16 million – $22 million, have so much violence that your head boggles? And these are the pictures making the most money at the drive-ins for our teen-agers, etc. The reason [censors] say something is because David is giving you artistry at the same time. He’s giving you feeling at the same time. He’s not just going ‘buh-buh-buh-buh-buh!’,” Ladd points her index finger like a gun, “so you walk out and say, ‘Boy, let’s go get some more popcorn and watch it again!’ He’s giving you art. And in the middle of art, you’re also seeing life and violence. It makes me sick.”

Not everybody is blinded by the film’s physical and emotional violence.

“I felt that the love story stood out a lot,” Cage says after viewing the film a second time. “I think that his movies are changing. This is the most romantic movie that David’s made, I think. What was originally a super-surreal style is now becoming more an observation on the psyche of people and, in a sense, that’s more fascinating. So he’s becoming more interested in people and the circumstances that people get into.”

So where does a film get funding if it’s too extreme for the majors? Producer Monty Montgomery, a Georgia transplant whose grandfather was a founding partner of Coca-Cola, was in charge of securing backing for the picture. With old Coke money to back him, Montgomery pursued film production in the early ’80s. With this experience he was able to back the $9.5 million production. Philanthropist Robert Woodruff is probably rolling in his grave.

Set in the South, Wild at Heart has a local appeal. The mood of all of Lynch’s films, from Eraserhead to Blue Velvet, was purportedly influenced by his brief but impressionable residency in Philadelphia. Is Wild at Heart his “Southern” picture?

“I lived in Virginia, and I went to school for one year in North Carolina, so I know a little bit about the South, but it’s not my Southern story. It’s just something that I read and I got hooked into,” he says.

He doesn’t feel Southerners are any different than the rest of America. “They just talk funny.”

Dern discusses Lula’s Southern heritage.

“I think there’s a lot in her. I’m from California, but I spent summers in the South and my mother and grandmother are from the South, and I have known many Southern belles in my day. I would not ever say that Lula was the next Scarlett O’Hara, the representative of the South. I think that there’s a lot of Southernness in her. Isabella Rosselini and I talk about this a lot. We think that Southern women and Italian women have a lot of similarities because there’s a flair for drama and emotion in these kinds of people. Lula kind of shares that. She feels so much that she feels like her brain is going to explode. And that’s that kind of drama.”

“The use of language is very Southern,” Dern continues. “Some of her use of humor and things like that. But other than that, she’s Marilyn Monroe with a little bit of Lucille Ball and little bit of Southern and a little bit of Laura. And there you get her.”

The cast, it seems, has a remarkably positive conception of the movie.

“I think the movie has a very good message. If there is a message that means something to me, it’s that love can survive in hell. Love, if it’s true can stay together no matter what the obstacles. That, to me, is a very simple and a very beautiful message,” says Cage.

Montgomery, the producer, offers an interesting perspective on the quirky appeal of Wild at Heart. “Following test screenings, 75 percent of the people rated the movie ‘excellent.’ These same people said they would not recommend it to a friend.” He compares this phenomenon to that of a person who goes to a strip joint. He may like it, but he won’t talk about it. It will be interesting to see what success Wild at Heart will meet.

The popularity of Twin Peaks is sure to convert a new generation of Lynch lovers. The film opened wide last Friday on more than 870 screens nationwide.

“I think when someone says ‘Hey, it’s jam packed with blood and gore. It’s action packed,’ you get a sort of type of audience to go to it,” says Dern. “Wild at Heart isn’t being sold as that, so I don’t know that it will get any more on that level.

“We were thinking the other day, this is kind of a summer movie. We’ve got sex, violence, it’s a road picture, good music. We never thought that we’d be making a regular Hollywood movie. Maybe Wild at Heart is just a mainstream movie,” she says with an impish twinkle in her eyes. “Maybe that’s what it is. Wouldn’t that be strange?”

![]()