The Burnham Pavilions

A summary document prepared for the Burnham Plan Centennial Committee

Finalized August 2010

What Do You Do to Mark the Centennial as a Moment to Advance Future Planning?

As early as 2003, various Chicago civic leaders, cultural institutions and universities began to discuss possibilities for commemorating the 100th anniversary of the 1909 Plan of Chicago. Under this amorphous Plan of Chicago Centennial Initiative, there was no shortage of ideas; Proposals ranged from hosting a skateboard competition in Burnham Park or decorating a Burnham-designed building to resurrecting the Department of Cultural Affairs’ 1999 Cows on Parade exhibit, this time with a Daniel Burnham theme. When the Chicago Community Trust came on board as a founding sponsor, it demonstrated that they could generate significant funding for a centennial with a lasting legacy. In late 2006, leadership for organizing and coordinating the Centennial was given to Chicago Metropolis 2020, a business-backed regional planning entity fittingly established by The Commercial Club of Chicago, who a century ago commissioned the 1909 Plan of Chicago.

In December 2006, the Burnham Plan Centennial Committee was created and would include: Millennium Park Inc. Board Chairman John Bryan, CM2020 President and CEO George Ranney, and Habitat Company President and CEO Valerie Jarrett as Co-Chairs; CM2020 Vice-Chair and Senior Executive Adele Simmons as Vice-Chair; and CM2020 Program Director Emily Harris as Executive Director. The 26 members of the Committee represented major companies, civic organizations and cultural and educational institutions from throughout the region. The Committee started to organize partners and commissioned a branding study to answer the question of what a centennial can be. In its early planning stages, the Committee sought to find a centerpiece – a bold, iconic focal point – for the region-wide Centennial, one that would emphasize the importance of boldly imagining a better future for all, as Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett had done with the bold plans and big dreams of their 1909 Plan. John Bryan insisted, “We need something physical to ‘stir men’s blood.’ People may not understand the concept of a Plan. They need something to touch, see and feel.”

In June 2007, the committee sponsored a brainstorming session, with participants brought together at the Department of Cultural Affairs by Nora Daley, Director of Outreach for Chicago Metropolis 2020. The creative brainstorming session was attended by: the public art and visual arts directors of the Department of Cultural Affairs; UIC School of Art & Architecture dean Judith Kirshner; MCA associate director Greg Cameron; then Executive Director of Millennium Park Helen Doria, with executive director of Millennium Park Inc. Ed Uhlir and Boeing Gallery curator Lucas Cowan; The Boeing Company Global Corporate Citizenship director Nora Moreno; arts patron Lewis Manilow; VSA Partners founding principal Dana Arnett; and a few Chicago installation artists. A number of ideas were bandied about, including sculptures in Millennium Park’s Boeing Gallery and temporary pavilions on the South Chase Promenade.

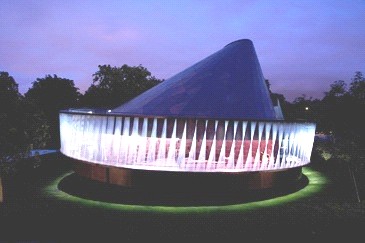

In October 2007 Centennial Vice Chair Adele Simmons, and Executive Director Emily Harris held a small follow up meeting with Art Institute of Chicago President Jim Cuno, Architecture and Design curator Joseph Rosa, Judith Kirshner and the new director of the School of Architecture at the University of Illinois at Chicago Robert Somol. It was at this meeting that the concept of bringing privately funded temporary pavilions more clearly emerged. The team zeroed in on the concept of temporary structures that exemplify futuristic designs inspired by the Burnham Plan. The eventual Burnham Pavilion concept is modeled after the annual Serpentine Gallery Pavilion commission in London (above), an ongoing program of temporary structures by internationally acclaimed architects that melds artistic and architectural experimentation. Also referenced is the P.S. One MoMA Contemporary Art Center and its annual temporary pavilions housed in its outdoor galleries (right).

In October 2007 Centennial Vice Chair Adele Simmons, and Executive Director Emily Harris held a small follow up meeting with Art Institute of Chicago President Jim Cuno, Architecture and Design curator Joseph Rosa, Judith Kirshner and the new director of the School of Architecture at the University of Illinois at Chicago Robert Somol. It was at this meeting that the concept of bringing privately funded temporary pavilions more clearly emerged. The team zeroed in on the concept of temporary structures that exemplify futuristic designs inspired by the Burnham Plan. The eventual Burnham Pavilion concept is modeled after the annual Serpentine Gallery Pavilion commission in London (above), an ongoing program of temporary structures by internationally acclaimed architects that melds artistic and architectural experimentation. Also referenced is the P.S. One MoMA Contemporary Art Center and its annual temporary pavilions housed in its outdoor galleries (right).

The Serpentine and the P.S. One MoMA are both temporary private pavilions located on gallery grounds. There have been temporary public pavilions in Europe as well. For example, a three-story public pavilion for the Luxembourg’s European Capital of Culture 2007 festival (left)  was a steel-tubed lookout tower built by Peripheriques Architectes. And Didier Faustino’s portable “Temporary Autonomous Zone” (below) was a temporary pavilion that traveled from France to Luxembourg. The Burnham Pavilions would distinguish themselves as being the first public temporary architectural pavilions in the downtown of a major American city.

was a steel-tubed lookout tower built by Peripheriques Architectes. And Didier Faustino’s portable “Temporary Autonomous Zone” (below) was a temporary pavilion that traveled from France to Luxembourg. The Burnham Pavilions would distinguish themselves as being the first public temporary architectural pavilions in the downtown of a major American city.

Executive Director Emily Harris said, “So often people hear ‘planning’ and they sort of yawn and say, ‘That’s for someone else to do.’ Really the whole idea is to get people to understand that it is their future we are talking about and that they need to jump on the bandwagon. So, the pavilions in Millennium Park are some very visible ways to do that [by urging people to] think outside the box, be creative and think about architecture and design, and think about what it is you’d like for the future.”

It was proposed that there be two pavilions with each school, UIC and IIT, having a relationship to one of them. The original concept was that students would be involved in the actual design process, but time constraints meant it was not feasible.

Harris introduced the concept to leadership of the Centennial committee including John Bryan who indicated support and asked her to pursue it with the City. Millennium Park was in transition at the time. The concept was first introduced to Helen Doria, and when Doria left as Millennium Park Executive Director, it was introduced in late 2007 to

City of Chicago Commissioner of Cultural Affairs Lois Weisberg, who designated as project manager Julie Burros, Director of Cultural Planning for the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs.

Burros said, “For a few years before the pavilion idea was hatched, I had been attending (mostly unproductive) Burnham Centennial Committee meetings. I knew that no matter what was done the City of Chicago would somehow have to be involved. Since I am an urban planner I was passionate about the 1909 Plan and was able to get the centennial year concept on the ‘radar’ of several city agencies. Little did I know I would have the opportunity to play such a major role in the signature project of the Centennial.”

Under the steering committee spearheaded by Emily Harris, Julie Burros, Joe Rosa and Ed Uhlir, the project began to take form. The new Pavilion team decided to involve architecture schools, so the heads of the architecture programs at the Illinois Institute of Technology and University of Illinois at Chicago were brought on to the team as university partners. Each school would be presented with a short list of prospective designers and asked to select the architect who would both design that pavilion and be involved in some way with that school’s curriculum.

Emily Harris said “It was a pleasure and an honor to work with Julie, Joe, Ed and the international architect team. We each brought a different set of skills and experiences to the project. Joe Rosa’s knowledge of design and relationships with the architects; Ed Uhlir’s inimate knowledge of every facet of the park and unique ability to get things done in Chicago; Julie Burros’ understanding of public programming and art from the perspective of the Department o Cultural Affairs as well as her project management and ability to cut through red tape were all essential to the project. I represented the perspective of the Burnham Plan Centennial Committee and our donors, and helped to provide overall coordination of the team as the “owners representative.”

Funding

Originally the committee proposed sponsorship of the the pavilions to major local corporation, but as the economic troubles of 2008 loomed, they declined to become the corporate sponsor. Millennium Park board chairman and Burnham Plan Centennial co-chair John H. Bryan stepped up, assembling a Burnham Leadership Group of civic leaders who would contribute $250,000 apiece to the project. Eventually, the Leadership Group comprised Mr.& Mrs. John H. Bryan, Mr. and Mrs. Wesley M. Dixon, Jamee and Marshall Field, Margot and Thomas Pritzker, Patrick G. and Shirley W. Ryan and the Crown Family. In addition British Airways provided an in-kind gift of the tickets needed to bring the architects to Chicago, Arcelor Mittal donated the structural steel needed for the UNStudio Pavilion and Marmon donated some of the aluminum to the Zaha Pavilion.

Concept

Daniel Burnham drew from Paris, Athens and Rome for his 1893 Columbian Exposition and from Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s plan for Paris in the 1909 Plan of Chicago. For this reason, the BPC Committee in March of 2008 sought the perspective of progressive international architects who best exemplified the Centennial’s forward-looking theme.

“Because Burnham interpreted Parisian streetscapes and Haussmann’s way of thinking, we thought the most logical thing to do was to invite two European designers to come and look at Burnham,” Rosa explained. “We compiled a list of avant-garde, buildable architects that we thought would be a great asset for a temporary pavilion in the city.”

Ed Uhlir expounded, “We looked at Pritzker Prize-winning architects and architects who hadn’t built before in the city. We thought it would be good to get architects from outside the U.S. to get a new perspective on where the art was going. The important thing was they hadn’t done work in Chicago and had to be cutting edge contemporary architects. Their reputation had to be now instead of in the past.”

Some of the modern, cutting-edge “starchitects” on a short list prepared by Rosa and Uhlir included the UK’s Zaha Hadid, the Netherlands’ Ben van Berkel, Austria’s Wolf Prix, and Switzerland’s Herzog & de Meuron. The lists were then presented to the collaborating schools. “The goal of connecting the architects to the schools” said Emily Harris, “ was to make sure that the next generation of architects could benefit, and that at every stage the Centennial would ‘give back’ to Chicago.”

IIT’s dean of Architecture Donna Robertson selected Zaha Hadid Architects, citing her interest in the way Hadid’s designs “harness the energy of the city and translate it architecturally.” Baghdad-born/London-headquartered Zaha Hadid recently had been honored with a 30-year retrospective at the Guggenheim, and her 2003 design for the Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati was lauded by the New York Times as “the most important American building to be completed since the end of the cold war.” In 2004, Hadid became the first female recipient of the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize.

UIC’s director of the School of Architecture Robert Somol chose Amsterdam-based UNStudio and Ben van Berkel, a rising star of inventive, computer-aided architecture, who had recently completed the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart (2006).

In April of 2008, Joe Rosa contacted the architects on behalf of the Centennial Committee and won their agreement, with “very little arm-twisting.” The architects were offered a $75,000 design fee and were advised to design with a $100,000 to 250,000 construction budget per pavilion. The architects requested a construction budget for double that amount, based on previous exhibitions and temporary buildings, bu the committee indicated that it was still fund raising and requested a design to fit the smaller budget..

On June 22, 2008, the committee announced the project to its partner organizations at a meeting at Spertus where the website was launched and information was shared about the overall Centennial. The Chicago Tribune announced that two architects, “paragons of the avant garde,” would be designing the temporary pavilions in Millennium Park as the focal point for the Centennial. Architecture critic Blair Kamin wrote that Hadid and van Berkel “will add sizzle to next year’s celebration of the Burnham Plan and may ensure that the centennial events – educational programs, arts events and open space projects – do more than take a nostalgic glance in the rear-view mirror.”

Pavilion Steering Committee member Ed Uhlir brought on Christopher Rockey – principal of Rockey Structures LLC, and associate professor at IIT – as the pavilions’ structural engineer. Rockey had worked on the Frank Gehry-designed BP Bridge in Millennium Park while an associate at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

Of the choice, Uhlir said, “Chris was involved in the structural engineering for Pritzker Pavilion. He and I both teach at IIT. He knows the park. You had to know the loading capacity in the park, and he had access to that. He didn’t have to reinvent the wheel.”

In early August of 2008 the Burnham Plan Centennial Committee had its first team meeting with the design architects in Chicago. Christian Veddeler and Wouter de Jonge of UNStudio and Thomas Vietzke and Jens Borstelmann of Zaha Hadid Associates convened at the Department of Cultural Affairs with the two universities, structural engineer Chris Rockey, local architects of record, and lighting consultant Daniel Sauter, an installation artist and Assistant Professor at the School of Art & Design at UIC.

The design architects were given a broad concept for the project, shown the site in Millennium Park and its footprint, given the caveat that Millennium Park structures cannot stand taller than Cloud Gate’s 33 feet. The construction budget stood firm at $250,000 or less for each pavilion.

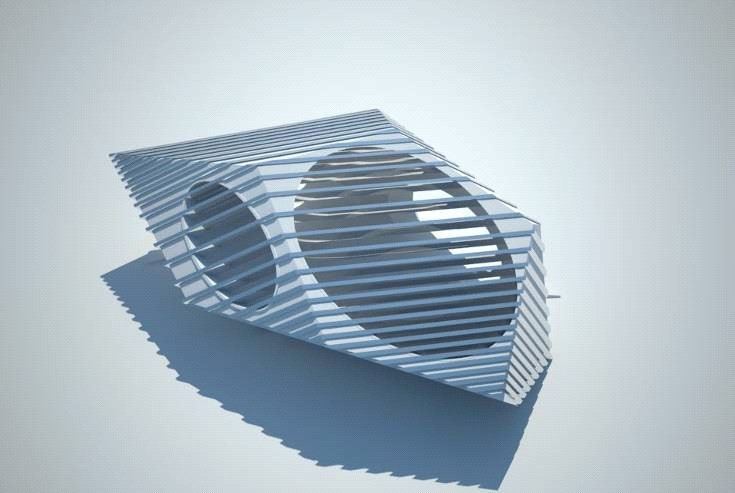

In conceiving their structures, both teams of design architects expressed how European architects are taken by the characteristically American grid layout of most cities, whereas Burnham was interested in the diagonals that opened them up. On September 10, 2008 the architects submitted their first concept sketches to the Burnham Committee, and the diagonal streets proposed in Burnham’s Plan of Chicago were points of reference for both. The diagonal rib-like structure of Zaha’s original pavilion was her tribute to Burnham. Van Berkel explained that his structure was all about the “diagonality” of the views of the city through the pavilion’s scoop-like openings.

UNStudio’s first submission had the cantilevered roof attached to the floor by only one supporting linear touch point. Structural engineer Chris Rockey suggested that it would not be feasible to support the 80 x 80-foot roof by one column, and from there van Berkel’s three-legged design evolved. With the horizontal planes of its base and roof, the UNStudio Burnham Pavilion nods to Chicago’s historical Prairie School of architecture, inspired by van Berkel’s teenage visit to Chicago when he first saw the cantilevered ceiling and roof eaves of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House in Hyde Park.

UNStudio’s first submission had the cantilevered roof attached to the floor by only one supporting linear touch point. Structural engineer Chris Rockey suggested that it would not be feasible to support the 80 x 80-foot roof by one column, and from there van Berkel’s three-legged design evolved. With the horizontal planes of its base and roof, the UNStudio Burnham Pavilion nods to Chicago’s historical Prairie School of architecture, inspired by van Berkel’s teenage visit to Chicago when he first saw the cantilevered ceiling and roof eaves of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House in Hyde Park.

“Chicago has had a great influence on me since I was younger and visited the works of Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan in the city,” van Berkel said. “Then when I was in Japan, I went to the Aisaku Residence by Wright and then that is when I decided to study architecture. I did not realize how influential Chicago architecture was until I traveled the world.”

For van Berkel, Burnham’s diagonal streets determined the shape of sculptural openings in the roof of his otherwise planar pavilion, functioning as frames for our skyline that draw our past into the present and future.

“Picking up on Burnham’s grid, we wanted to play with the diagonality of the site to start to open up the grids,” van Berkel said. “The diagonal quality is recognized both in plan and section of the city. When in the pavilion you can see through the ceiling as petals tear into it allowing for views of the top of the skyline as opposed to only having a horizontal reading of the city. These petals start to transform the pavilion from a harsh box organization to a softer infrastructural one. This transformative quality is the essence of the pavilion.”

Zaha Hadid’s original concept was for a rigid, angular structure with a curved soft form inside, featuring seating and a screen for digital programming. The structural ribs and slotted windows in the roof were angled along an imaginary line that Hadid extended from one of Burnham’s proposed diagonal streets in the Plan of Chicago directly onto her Pavilion’s footprint in Millennium Park. The job for the solid pavilion was bid out to contractors who came back with an estimate of ten times the initial budget. Hadid Pavilion architect of record Thomas Roszak suggested the notion of a fabric-covered structure. Hadid’s team went back to the drafting board and, with that in mind, redesigned the pavilion to be made of fabric in its final cocoon-like shape.

Zaha Hadid’s original concept was for a rigid, angular structure with a curved soft form inside, featuring seating and a screen for digital programming. The structural ribs and slotted windows in the roof were angled along an imaginary line that Hadid extended from one of Burnham’s proposed diagonal streets in the Plan of Chicago directly onto her Pavilion’s footprint in Millennium Park. The job for the solid pavilion was bid out to contractors who came back with an estimate of ten times the initial budget. Hadid Pavilion architect of record Thomas Roszak suggested the notion of a fabric-covered structure. Hadid’s team went back to the drafting board and, with that in mind, redesigned the pavilion to be made of fabric in its final cocoon-like shape.

“Early on when we all agreed to change the concept of the structure and materials, Zaha and her team insisted to re-think and test all of the concepts all over again,” Roszak said. “They did not just side step and make some unenergetic adjustments. A completely new (and better) building was created. It was clearly better and it gave us all chills when we knew we are a part of something world-class and super-cool. Looking back it was all part of a natural plot trajectory that this pavilion had to go through to get built and be the great design that it is. Daniel Burnham would be proud.”

“Fabric is both a traditional and a high-tech material whose form is directly related to the forces applied to it – creating beautiful geometries that are never arbitrary. I find this very exciting,” Hadid enthused.

In late September of 2008 the architects submitted their final schematic designs. All parties agreed that the construction budget needed to be increased and the Centennial Committee agreed to continue to raise funds and seek in-kind contributions to make the pavilions possible with leadership from Adele Simmons and john Bryan.

Upon completion, Hadid ruminated, “[For civic projects in the 20th Century] the client became the people. Burnham’s Plan of Chicago reflected this and his Plan’s systems and diagrams for Chicago have informed the pavilion’s design…. The design responds to the program and to the site at the same time. All the forces operate at once to come up with one thing, and we investigated Burnham’s organizational diagrams for the city to develop the Pavilion’s design. As we’ve done in our buildings, where elements fit together to form a continuum, we’ve applied these 3D design techniques to the Pavilion. Using these techniques, we can do something radically different than what we saw at the beginning of the 20th Century when Burnham’s Plan was published.”

Curricula

Because of the Zaha Hadid pavilion’s planned video installation, IIT and ZHA offered two studio courses in 2008 conducted by architect Dirk Denison and film critic Jonathan Miller centering around the notion of visual media as an architectural element. The curriculum was highlighted in Architect’s November 2008 Education Issue for its progressive approach. On September 10, 2008, Zaha Hadid Architects associates Thomas Vietzke and Jens Borstelmann conducted popular free public lectures titled “Nordpark: Continuity” and “Chanel Mobile Art: Digital Design to Fabrication” on the IIT campus.

Subsequently, Somol, director of the School of Architecture at the University of Illinois at Chicago, introduced van Berkel for a lecture on April 14, 2009 as part of the UIC School of Architecture Spring Lecture Series. During the van Berkel talk, the architect explained how he was influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture he experienced when visiting Chicago at age 19. He worked with students on their publication Fresh Meat, and architects from UNStudio did three desk critiques with UIC students throughout the year.

Announcement

On April 7, 2009 Emily Harris of the Burnham Plan Centennial Committee, curator Joe Rosa and project manager Julie Burros of the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs unveiled the architects’ renderings in a public forum at the Chicago Cultural Center consponsored by Alderman Brendan Reilly, Tom Wolf of Friends of Downtown,. In attendance were more than 200 people representing donors, University representatives, architects of record, staffers from CMAP, members of the Friends of Downtown and the public. “This was the first chance we got to describe to the public and the press that the entire South Chase Promenade in Millennium Park was going to be like a big outdoor museum exhibit with interpretive panels to explain everything, an interactive digital kiosk, ‘Ask Me’ volunteers, a summer-long series of programs called ‘Talks With The Team,’ a nightly light show, an immersive film experience and, of course, the two pavilions,” noted Burros.

On April 7, 2009 Emily Harris of the Burnham Plan Centennial Committee, curator Joe Rosa and project manager Julie Burros of the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs unveiled the architects’ renderings in a public forum at the Chicago Cultural Center consponsored by Alderman Brendan Reilly, Tom Wolf of Friends of Downtown,. In attendance were more than 200 people representing donors, University representatives, architects of record, staffers from CMAP, members of the Friends of Downtown and the public. “This was the first chance we got to describe to the public and the press that the entire South Chase Promenade in Millennium Park was going to be like a big outdoor museum exhibit with interpretive panels to explain everything, an interactive digital kiosk, ‘Ask Me’ volunteers, a summer-long series of programs called ‘Talks With The Team,’ a nightly light show, an immersive film experience and, of course, the two pavilions,” noted Burros.

Of his 80 x 80-foot structure’s two parallel planes joined by three curving scoop supports, van Berkel’s prospectus explained, “The UNStudio Burnham Pavilion relates to diverse city contexts, programs and scales. It invites people to gather, walk around and through and to explore and observe. The pavilion is sculptural, highly accessible and functions as an urban activator.” The UNStudio pavilion was designed for total accessibility, able to be walked on with a ramp designed into the platform to make it wheelchair accessible.

Of her 70-foot long tented “cocoon,” Hadid wrote, “The pavilion is composed of an intricate bent-aluminum structure, with each element shaped and welded in order to create its unique curvilinear form. Outer and inner fabric skins are wrapped tightly around the metal frame to create the fluid shape. The skins also serve as the screen for video installations to take place within the pavilion. Zaha Hadid Architects’ pavilion also works with the larger framework of the Centennial celebrations’ commitment to deliberate the future of cities. The presence of a new structure triggers the visitor’s intellectual curiosity whilst an intensification of public life around and within the pavilion supports the idea of public discourse.”

Hadid’s pavilion would be made of totally recyclable materials that, in theory, could be unzipped, dismantled and reinstalled elsewhere as a traveling exhibition after the Centennial.

At the forum, Committee Co-Chair John Bryan said, “Public art and visionary design are necessary for any city intending to play a global leadership role in the 21st century. These two Burnham pavilions make bold statements to the world, as did Millennium Park, about Chicago’s confidence in its future.”

Co-chair George Ranney said “While the Millennium Park pavilions create a focal point for the Burnham Centennial, our underlying intent in commissioning them is to motivate the millions of people who experience them to get personally and actively involved in enhancing our regional environment, improving our quality of life, and insisting that our leaders do what is necessary to keep our region economically prosperous. The business community has invested in the Centennial because it knows that what is at stake here is metropolitan Chicago’s ability to compete globally for jobs and investment.”

Centennial vice chair Adele Simmons said, “While the Burnham Centennial is indeed about the serious business of building a better future, it will also be entertaining, educational and enjoyable. More than 220 organizations throughout the three-state region will be offering hundreds of programs, exhibits, and events that use the accomplishments of Chicago’s audacious past as inspiration to achieve a new generation’s big dreams for the future. The energy and excitement of the Burnham pavilions will inspire people to think ‘out of the box’ about our metropolis and our future.”

Hard costs, including architects fees and constructions costs, were approximately $1 million for the two pavilions. Ultimately the budget for the opening events in Millennium Park, programming including interpretive panels and the film inside the Zaha Pavilion, rental of projection equipment, security, brochures, staffing and other elements added another $1 million. Funding was provided by private donations, including the Burnham Leadership Group, opening sponsor National City Bank (now PNC), airline sponsor British Airways and Steel sponsor Arcelor Mittal.

Construction

Starting with the architects’ 2008 site visit, architects of record were brought on who would supervise the construction. Doug Garofalo – principal of Garofalo Architects and a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Architecture – was hired as the UNStudio architect of record.

“I agreed to do it is because of UNStudio; I’ve met Ben van Berkel in the past and he’s a great guy. That alone was good enough for me,” Garofalo said.

“When the designs came in, everyone was in love with them, including us. The technology of it all was amazing, not without any pressure. There are moments when you’re looking at something and you think there’s no way it’s going to look like their drawings, but you work on it and it turns out pretty well. It became an issue of how to get it done with the quality and detailing they were interested in. It was a real push to get it done on time. I will say this would have been much more difficult if it had to be something permanent.”

Thomas Roszak – principal of Thomas Roszak Architecture, LLC and graduate of IIT – was brought on as the Zaha Hadid architect of record. Roszak recalls, “We were pushing the technology of the virtual with Rhino (computer rendering software) and the physicality with a fabric enclosure and an aluminum structure.

“Zaha Hadid and her team, headed by Thomas Vietzke and Jens Borstelmann, are not only architects; they are equally artists and scientists. They worry about all the things that architects worry about, but raised to a higher degree. The natural shapes are not arbitrary or purely artful, they are strict and serious and inspirational and insanely beautiful. The designs are based on complex curved shapes where the inclination of the curves are pure mathematics and not based on digitizing scraps of cardboard or clumps of clay. Every available point in space on the site is thoroughly analyzed…should it be part of the building or not. What color should that point in space be, what texture should it have, should light touch it?”

Structural engineer Chris Rockey articulated the difference between the two architects’ processes. “UNStudio was a very traditional project. The design architects produced a digital model, architect of record Doug Garofalo created production drawings and Chris did the construction drawings. They went out for bids and went out to the City for permit. Zaha Hadid Architects, on the other hand, was more of a design-build. They work in model form and in digital form. Tom Roszak did not produce blueprints or detail drawings, rather snapshots from models. The builder hired their own engineering services; we acted as the owner’s rep and took full responsibilities.”

As the designs for the pavilions became more fully realized, lighting design came more to the forefront. Burros elaborated, “There was a strong desire to create a different experience at the pavilions for daytime visitors versus nighttime visitors, as well as to introduce an element of interactivity. Lighting was the ideal way to accomplish that.”

“I was first introduced to the project during the initial briefing session in August 2008,” explains lighting consultant Daniel Sauter. “After UNStudio solidified the pavilion’s geometry in November 2008, it became clear that the perfectly seamless and dynamic transition between the horizontal base and the roof plane would be both an important signature feature to highlight, and a challenge from a lighting design perspective. In close discussion with UNStudio and Garofalo Architects, I worked with Tracey Dear to realize a homogeneous plane of light (‘sandwiched’ between the roof and the base), best suited to underline the seamless nature of the architectural design.”

In January of 2009, exterior lighting innovator Tracey Dear, an Oak Park-based architectural lighting designer, was brought onto the project. Dear’s Chicago credits include the lighting design of 11 bascule bridges over the Chicago River as well as the historic Wrigley Building. Dear conceived a lighting grid around the South Chase Promenade that would illuminate both pavilions. Dear also designed an elaborate array of color transitions to be projected upon the Hadid Pavilion.

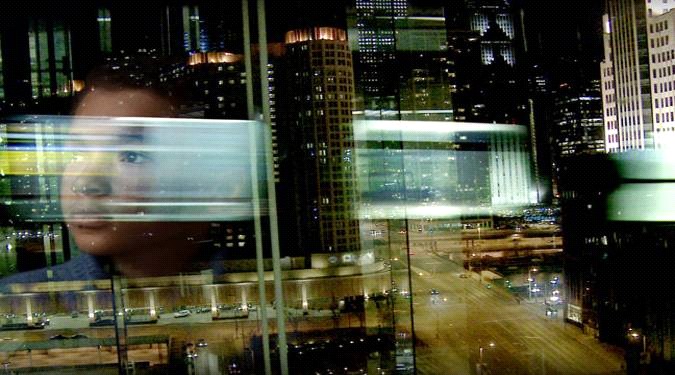

For the UNStudio pavilion, Sauter and Dear proposed a grid of 42 LED lights enhanced with motion sensors to be embedded in the pavilion floor that, at nighttime would give the glossy white structure an ethereal glow. The shifting colors, triggered by people walking on the pavilion. were keyed to the color palette of the famous Jules Guerin illustrations in the original Plan of Chicago. During the pavilion’s construction, Daniel Sauter created models and tests that were approved by UNStudio.

Sauter explained, “The stage-like openness inviting thousands of visitors into the pavilion provided a great opportunity for us to actively engage visitors in the exploitation of the space through an interactive lighting system. I designed a sophisticated light sensor system embedded in the pavilion base (directly on the light fixtures) to detect the presence of visitors inside the pavilion. Once visitors stepped over the fixtures, they triggered a dynamic complementary color transition, spreading from the visitor over the entire pavilion. This response from the 42 LED fixtures gave the impression of an imprint, an ongoing ‘heat map,’ derived from the visitors’ movement through the space. The color scheme itself was derived from watercolor illustrations originally published in Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago, functioning as a subtle but also specific conceptual link to the Centennial theme.”

Construction of the UNStudio Pavilion was headed up by Third Coast Construction, a local self-described green contractor. Using steel donated by Chicago-based ArcelorMittal, the pavilion was built on site in Millennium Park beginning on May 5, 2009. Despite its 49 tons of steel, the glossy white structure seems airy, made of plywood ribs and a plywood surface atop a heavy steel skeleton. The pavilion was built to be de-constructed and recycled at the end of the summer.

The tent-like Zaha Hadid Pavilion would be formed of 1,600 yards of fabric mounted on a three-ton skeleton of aluminum tubing partially donated by Marmon/Keystone Industries. Evanston-based TenFab, a creator of tensioned fabric designs for trade shows, was hired to be its fabricator. In February of 2009, construction for the Hadid Pavilion began offsite in a warehouse in Lincolnwood where TenFab cut, bent and started to piece together the aluminum frame, comprising 24 ribs connected by 7,000 uniquely shaped parts. The complexity of the job, however, put TenFab behind schedule, and on June 6, less than two weeks before its scheduled debut in Millennium Park, the team discovered that TenFab was too far behind to make the opening. That weekend, the decision was made to move the unfinished project to the Park so if it wasn’t going to make its scheduled opening date, at least its completion of construction could be observed by the public. Immediately after the June 19 UNStudio opening, the BPC team met with TenFab to come up with a revised schedule for completion of the Zaha Hadid pavilion, which proved to be too far into the future and TenFab resigned the commission.

Aaron Helfman, owner of TenFab Design, said, “I wish it had worked out differently, but nobody knew where it was going. It was like a journey we took together, and then we were like, ‘Oh my God.’ It turned into a much greater and more complex endeavor than anybody had realized.” Helfman told the Chicago Reader that nobody on the planet had done anything like this “amazing structure” before—”the scale and scope, the complexity. And then you throw in a three-month window to make it. The time frame was impossible.”

On June 24, the Burnham Committee accepted bids from other firms and the project was awarded to Elgin-based Fabric Images who assured they could get it sewn up in 30 days. The new firm worked 12-hour shifts seven days a week, bringing industrial sewing machines on-site and a crew of seamstresses to build the skin directly onto the structure.

“Each panel is zippered into place, with the seams fitting precisely over the curving aluminum ribs underneath. It’s like the scales of a fish or a form-fitting dress,” explained Fabric Images general manager Gordon Hill, a UIC graduate. “We had to add about 300 crossbars and weldments, and redo 19 out of the 24 trusses, along with adding the fabric to it. We kind of re-engineered it.”

Lynn Schoenknecht, who led the sewing team, recalls, “The challenge of what we were facing with a 30-day deadline was exhilarating! The brainstorming each morning on the drive in was an important part of each day. The teamwork – the family that we developed into – was special for me, too. Oh, yes, there were challenging days to be sure; but the overall experience was a ‘once in a lifetime.’”

Following in the Chicago tradition of Burnham’s own 1893 Columbian Exhibition and, more recently, Millennium Park, the Zaha Hadid Burnham Pavilion took longer than anticipated to complete, but finally opened to the public on August 4, 2009. “This is an artistic achievement of global proportions,” praised Emily Harris. “It is fabulous. Special thanks go to Fabric Images of Elgin for jumping in to complete this project as envisioned by Zaha Hadid.”

The Hadid Pavilion construction delay cost roughly $150,000 in overages from its allotted $500,000 budget. Harris quipped to the Chicago Tribune that given all the publicity the Pavilion had been getting, it could be resolved by shifting money from the advertising budget.

Opening

Opening-weekend events were sponsored by National City, now a part of PNC. The UNStudio Burnham Pavilion welcomed its first visitors on the evening of Thursday, June 18 during a private donors reception attended by van Berkel, the Zaha Hadid design team and more than 500 donors, civic leaders and dignitaries. The public opening occurred at noon the following day on Friday, June 19. Among the earliest visitors were a bride with her bouquet and groom in his military dress uniform having wedding pictures taken against the pristine white backdrop of the UNStudio Pavilion. The pavilion opening was followed in the afternoon by a free Architects Symposium with design architect Ben van Berkel, Hadid associate Thomas Vietzke, Robert Somol, Donna Robertson and Joseph Rosa directly across the street at the Art Institute. At the symposium, Somol quipped about the Ben van Berkel pavilion: “It’s as if Mies ate Goldberg, or Goldberg was having his revenge on Mies from the inside, but which one I’m not sure.”

On Friday and Saturday nights, 20,000 people, including Governor Pat Quinn, braved the rain and came out to Jay Pritzker Pavilion for a free celebratory concert at the Grant Park Music Festival. Outside the glow of the pavilions, the concert featured the world premiere of Michael Torke’s Plans, a newly commissioned work for symphony and chorus, inspired by the Plan of Chicago. The 40-minute choral work draws its text from the quotation attributed to Burnham: “Make no little plans, they have no magic to stir men’s blood,” with each of the five movements based on a sentence from that speech. Key words such as “order” and “beauty” are repeated by the chorus and soloists Jonita Lattimore soprano and tenor Bryan Griffin.

Pavilion Programming

At nightfall from August 4-November 1, a film installation titled “Chicago Past, Present and Future” was projected onto the Zaha Hadid Burnham Pavilion’s fabric interior from three different points inside the structure, two from the front and one from the rear of the screen, creating a fully immersive, intermittently 3-D effect. The film, running on a continuous loop, impressionistically reflects Chicago’s transformation from 1909 to the present, and includes the voices of people throughout the Chicago region sharing their visions of the future. The 7½-minute, wide-screen video is by Chicago-educated/London-based video artist Thomas Gray of the Gray Circle with a soundtrack by Lou Mallozzi of Chicago’s Experimental Sound Studio.

At nightfall from August 4-November 1, a film installation titled “Chicago Past, Present and Future” was projected onto the Zaha Hadid Burnham Pavilion’s fabric interior from three different points inside the structure, two from the front and one from the rear of the screen, creating a fully immersive, intermittently 3-D effect. The film, running on a continuous loop, impressionistically reflects Chicago’s transformation from 1909 to the present, and includes the voices of people throughout the Chicago region sharing their visions of the future. The 7½-minute, wide-screen video is by Chicago-educated/London-based video artist Thomas Gray of the Gray Circle with a soundtrack by Lou Mallozzi of Chicago’s Experimental Sound Studio.

More than a dozen informational panels adjacent to the pavilions were designed to inspire visitors to engage with the Burnham Plan Centennial and opportunities to shape the future of Metropolitan Chicago. A touch-screen kiosk installed by the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) allowed visitors to make choices about our quality of life by interacting with the regional GO TO 2040 plan.

Throughout the summer, the Pavilions hosted free bi-weekly Talks with the Team, a series of free informal tours of, and talks about, the Burnham Pavilions featuring the staff and professionals involved with the project. The tours gave the public the opportunity to learn directly from the insiders about the planning, design, construction, techniques, artistry and technology involved in making the Burnham Pavilions a reality. Each team member brought their own emphasis to the talk and shared their unique perspective.

A corps of more than 60 volunteers who share an interest in urban planning, Daniel Burnham, Chicago history, Millennium Park, and architecture and design, was trained as docents in a collaborative effort with the Burnham Plan Centennial Committee and the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs. These “ASK ME” docents were at the pavilions daily to inform and answer questions about the Zaha Hadid and UNStudio/Ben van Berkel pavilions, as well as the 1909 Plan of Chicago and the Burnham Plan Centennial.

A corps of more than 60 volunteers who share an interest in urban planning, Daniel Burnham, Chicago history, Millennium Park, and architecture and design, was trained as docents in a collaborative effort with the Burnham Plan Centennial Committee and the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs. These “ASK ME” docents were at the pavilions daily to inform and answer questions about the Zaha Hadid and UNStudio/Ben van Berkel pavilions, as well as the 1909 Plan of Chicago and the Burnham Plan Centennial.

On October 21, 1300 school children from 32 area schools visited the pavilions on a Millennium Park Field trip.

The occupiable pavilions proved to be irresistibly interactive. From day one, visitors ascended the van Berkel platform to explore the design, check out the views, or just sit on the platform to eat lunch or read a book. Children were drawn immediately to the “scoops” which, to them, resembled playground slides or the curved banks of a skate park. The pavilions were magnets for more spontaneous activity, including ballroom dancers who adopted the colorfully illuminated UNStudio as a tango platform throughout the summer, musicians who used the raised platform as a stage, chalk caricaturists who used the Pavilion’s shade as a home base and an invasion of Charlie Chaplin impersonators from the Great Performers of Illinois festival.

“There were 10 Asian girls (obvious tourists not locals), maybe about 20 years old, who stood on the platform of the van Berkel and created different words using their arms, legs and torsos, words such as “Chicago” and “welcome.” The white made a nice background,” said docent Janet Elson.

Pavilion docent Lynn Neils recalls, “I would have to say my fondest memory was on my first day of volunteering when a young woman marched up to the van Berkel pavilion, turned around and started singing opera arias. After about 15 minutes she quietly walked away. Proof the pavilions inspired each of us in a different way.”

Attendance

Between June 19 and November 1, 2009, an estimated one million people visited the Burnham Pavilions in Millennium Park. Some happened upon them unintentionally, whether straying over from “Cloud Gate,” taking a lunch break in the park, wandering down the Nichols Bridge from the Art Institute or en route to a concert in Pritzker Pavilion or Grant Park. Others made the trip especially to see the temporary Pavilions, some from great distances. There were a number of wedding parties photographed at the Pavilions as well as one senior citizens cycling club who pedaled down the lakefront from the North Shore.

Anecdotal surveys conducted by Burnham Pavilion docents suggest that 40% of the visitors came from the Chicago Region, 35% from elsewhere in the U.S. (as far away as Hawaii) and 25% from outside the country, including Japan, Germany, Austria, Greece, India, Switzerland and Canada. Roughly 60% of the visitors said they happened upon the Pavilions by chance while visiting Millennium Park, 30% said they came specifically for a Talk With the Team or a docent tour (most citing Blair Kamin’s blog or other media references) and 10% came over before or after visiting the Art Institute’s Modern Wing.

Reaction

Public reaction to the Pavilions was overwhelmingly positive. Those who spoke to the docents most often praised their interactivity, inspiration, magnitude and futuristic designs.

“Many people spent a great deal of time reading the informational placards and the brochures, and many people asked me fascinating questions, about Burnham, Chicago, the Plan, the future, about what the pavilions meant, what Hadid and Van Berkel had to do with Chicago, etc.,” Pavilion docent Gabe Labovitz said. “I interacted with people from all over the country and the world (Ireland, Japan, China, Israel, Greece are nationalities of people who come immediately to mind), took their pictures and had my picture taken with them.”

Children expressed their approval physically, running through the structures, playing hide and seek, and feeling the textures. Precocious kids pronounced that walking into the Hadid pavilion reminded them of going into the belly of a whale or a chrysalis. Others said the pod reminded them of a seashell, or the Sydney Opera House. Adults opined that Hadid’s tent resembled a Nautilus, an egg, a bike helmet, a dinner roll and even a hornet.

The delicate white interior skin of the Hadid Pavilion initially experienced a good deal of wear and tear from visitors who felt compelled to touch and even sit on it. The UNStudio Pavilion’s steep curved scoops proved irresistible to teenage and adult climbers. Guerilla incidents include dozens of teenagers from the June BMX Open in adjacent Grant Park who breached the roof after hours to skateboard down the ramp-like pillars, leaving gouges and scuffs on the walls. More than 100 people scaled the roof on the evening of July 3 for a better view of the Independence Day fireworks over Lake Michigan. As a result of the wear and tear, the pavilion was closed the weekend of August 9 for a new coat of paint and repairs. The placement of white stanchions at the base of the columns successfully solved the climbing problem for the remainder of the summer.

The Centennial Committee learned a valuable lesson that crowds at Millennium Park are accustomed to interacting with the artwork, and climbing is to be expected. Museum-quality artwork requires museum-standard security. Issues were controlled when security was increased to included dedicated security guards during peak visiting hours. In addition, theater-style plastic stanchions were placed in front of the UNStudio “scoops” and around the interior perimeter f the Zaha Pavioin’s curving fabric walls to stop climbing and stem foot prints.

“There is a special reward you get from making something that is free and given to the public,” said Burros. “You have to let them go, give them up, and they take on a life of their own once in the hands of the public. It was endlessly fascinating to observe how people reacted, interacted, admired, photographed, nicknamed, climbed on, and just took ownership of the pavilions.”

Detractors included one man who said that he had just returned from Europe and didn’t like the contemporary designs; He would have preferred a Beaux-Art design for the Chicago pavilions. (It should be noted that he also spent 10 minutes photographing the structures). Another woman volunteered that she was not impressed by the project until she was given an explanation of their context.

Globally, laudatory pictorial features about the Burnham Pavilions appeared in glossy magazines from Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, Russia, France, The Netherlands, Denmark, Great Britain, South Africa, Brazil, Mexico and Canada, giving them international exposure. Domestic press reviews of the Pavilions were also (mostly) favorable.

Time magazine on Hadid:

“Hadid is a big admirer of Rei Kawakubo, the Japanese fashion designer behind Commes des Garçons, and her zippered pavilion definitely had an architecture that seems to be playing games with certain kinds of ingeniously constructed clothing. It’s another of Hadid’s coiling ‘liquid forms’ that brings to mind urban street patterns, but also in this case seed pods, pontoon fenders, jet engines and, oddly enough, one of Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Cars.”

Time magazine on UNStudio

“With the way it plays its billowing middle forms against its rectilinear roof and platform, like a two-sided cookie with a marshmallow center, it also seems to be a commentary on the two main kinds of architectural form — straight lines and flowing ones. And especially because of that all-white palette, the color associated with Le Corbusier, I thought of it as a hybrid of Corbu’s right-angled Villa Savoie period and his later, much more swelling Ronchamp moment. Then again, with its big creamy udders it also seemed to be playing games with Surrealist bio-morphism and maybe even the idea of sensuality squeezed by rationality.”

The Wall Street Journal on Hadid:

“Hadid’s digitally-designed pavilion features fabric stretched across aluminum ribs that give it an eerie solar-looking space ship effect.”

Gapers Block on UNStudio:

“The platform is actually a smartly designed bench intended to persuade park visitors to linger. This platform also gives the plenum space needed for dazzling night-time lighting effects. Moving around the drooped openings, the massive cantilevered roof structure immediately recalls Frank Lloyd Wright’s ability to compress and expand space with horizontal planes. To that effect, UNStudio’s effort to ‘surprise us’ with views of the city is both successful and legitimately urban.”

Gapers Block on Hadid:

“The ingenious system of fabric panels zippered together allows the cloth a snug fit over the bent aluminum frame. The zippers end up working with the hidden structure to create a system of contours that reinforces the futuristic shape… While a reference to Chicago’s diagonal streets is mentioned in the design’s explanation, it is only until a video is played on the interior that the pavilion’s connection to Chicago seems more than arbitrary. The video itself is wonderfully engaging and informative, and the interior space provides a unique theater; but the sculpture’s role is little more than a glorified movie screen.”

Chicago Tribune on UNStudio:

“A computer-age marvel. Built on a steel frame, it has a skin of glassy white plywood that starts off in familiar right angles and transforms into voluptuous double curves of bent plywood…. with three scoop-like forms that van Berkel’s project architect, Christian Veddeler, compares to lips or eyebrows.”

Chicago Tribune on Hadid:

“It’s a virtuoso display of structure, space and light. With its arresting combination of naturalistic forms and alien shapes, plus a dazzling video installation, the pavilion does exactly what it’s supposed to do: invite us to boldly contemplate the future, just as Burnham foresaw a better Chicago…. The pavilion’s north entrance… resembles a shark’s mouth, ready to swallow you. The entire pavilion, with its curving forms and openings, suggests a conch shell. The whiteness of the pavilion and its organic shape seem appropriate, given that it sits in a waterfront park. It’s a mix of alien object and familiar imagery.”

Chicago Reader on the Pavilions:

“Looks like a grounded blimp parked next to a playground slide gone wrong.”

Summary

The air turned cool, The Burnham Pavilions officially closed to the public on November 1, 2009. They had been lauded locally and celebrated worldwide, putting Chicago and its Centennial on the radar in architectural digests and glossy design magazines. It had been an international collaboration that provided local architects and engineers the opportunity to collaborate with world-renowned European architects.

“This was an exciting project, doing stuff with a complex geometry,” structural engineer Chris Rockey recalls. “UNStudio was rewarding because it was a true collaboration. We had structural input which altered the design. There was back and forth.

“Zaha Hadid was exciting because of the material. Zaha Hadid Architects were more like ‘This is what you’re going to build.’ When it went to fabric, those guys nailed it. Zaha Hadid was interesting because we’ve never done a fabric structure or an aluminum structure and that was pretty exciting.”

Hadid Pavilion architect of record Thomas Roszak enthuses, “What a treat to be involved in something that is all about doing supremely good architecture. It is about commodity, firmness and delight. Capital D.”

UNStudio architect of record Doug Garofalo says, “It was very memorable. We learned a lot from all sorts of different people. We got to collaborate with one of the best architects in the world. All of those things combined were pretty amazing.”

“I had a great deal of fun, meeting the architects. I had them over to dinner a couple of times at my house, “says Ed Uhlir. “It’s unfortunate that Zaha never got here, but Ben van Berkel was an interesting guy.

Uhlir also felt that the pavilions were a a welcome addition to tourism in general and Millennium Park in particular. He recapped, “Seeing people enjoying the pavilions, that was certainly a benefit, as I love to see people enjoying Millennium Park. In 2009 a lot of people were unemployed. It’s a free park and there are lots of things you can do that don’t cost you anything. This of course added to that.

“Initially I wasn’t sure how much people would be interested, but it proved me wrong. Certainly the architecture community knows about Zaha and van Berkel, but the public doesn’t. The public was learning about Burnham, number one, and learning about the theory behind the two pavilions. People were excited about the shapes. We had a hard time keeping people from climbing them. People were really engaged. I was out there and saw one woman about 28 years old standing on top of the pavilions. She had obviously run up the scoops. I told her to get down. She told me that Ben van Berkel told her she could do it. Actually, Ben van Berkel encouraged people to walk on the platform. That was an interesting phenomenon. There were performances there. It certainly added another element to the park.”

Most importantly the Burnham Pavilions successfully served as a focal point for the Centennial that engaged the public and fostered discussion of Chicago’s history and possibilities for the future.

“All summer long people in the park would ask me ‘What is it? What are they for?’” recalls Julie Burros. “My standard answer always was ‘This is supposed to look like the future.’ Rather than go into a long explanation about Burnham and the Plan or the architects, it was the one thing I could tell to anyone and they would instantly get it.

The Pavilions far exceeded our expectations” said Centennial Executive Director Emily Harris. They generated unbelievable local excitement and worldwide press well into 2010. As of August 2010, they are still being nominated for international awards.”

“Like the spectacular water colors that illustrated the 1909 Plan, the Pavilions’ cutting edge design created a focal point for the Centennial’s extensive programs. People danced, they climbed, they touched and they looked in wonder at the innovative forms and cutting edge video that invited new thinking about form and the urban context. Many lingered to read the interpretive panels placing these monuments to futuristic thinking in the context of the Burnham Plan and the region-wide Centennial. While the pavilions generated extensive local and worldwide media attention, they also brought focus to hundreds of other Centennial events, including the local architects’ visions included in the Big Bold Visionary exhibit at the Chicago Tourism Center; the Chicago Architecture Foundation’s Model City exhibit; and the Make Big Plans exhibit at 67 libraries throughout the region.

With the Pavilions at the heart, the region took advantage of the Centennial deadline to affirm commitments and to take action. Legacy projects include curricula, progress on new parks, trails and preserves, on-line exhibits, archives and books. The greatest lesson of the Centennial, perhaps, is that the “spirit of Chicago” that imbued the Plan continues to inspire the region with a will to roll up our collective sleeves and get things done. The outpouring of interest and attention in the Plan’s 100th year, demonstrated that we can use collective public events to share diverse perspectives and knowledge as we harness our energy to get results. The pavilions were temporary, but they embodied this spirit of innovation and created a tangible place to demonstrate Chicago’s commitment to bold design and big dreams for future that is at once democratic, sustainable and beautiful.

On behalf of the Burnham Committee and staff, it was an honor to be involved.”

This document was prepared by Rob Walton under the direction of Emily Harris in spring 2010. Rob served as coordinator of volunteers for the Pavilions and assisted with communications on the Centennial staff during the fall and winter of 2009/2010. This paper is an internal document prepared to record the process of building the pavilions for the Centennial Committee, and for future researchers using the Burnham Centennial archive at the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries of the Art Institute of Chicago

Emily Harris, August 2010